All Aboard!

One fateful day, a ship set sail for England from the east coast of America. Aboard this vessel, invisible and unnoticed, were a group of silent killers. The devastation they unleashed would destroy livelihoods and ruin whole regions of Europe.

The precise date of this journey is unknown, but it was in the late 1850s, when it was common practice for European vine-growers to import vines from America. The growers did not know that they were also importing the deadly yellow lice carried on the roots of the native American vines. And whilst the American vine, used to being assaulted by these tiny insects, had developed ways to resist them, its European cousin, the wine-producing vine Vitis vinifera, was defenseless.

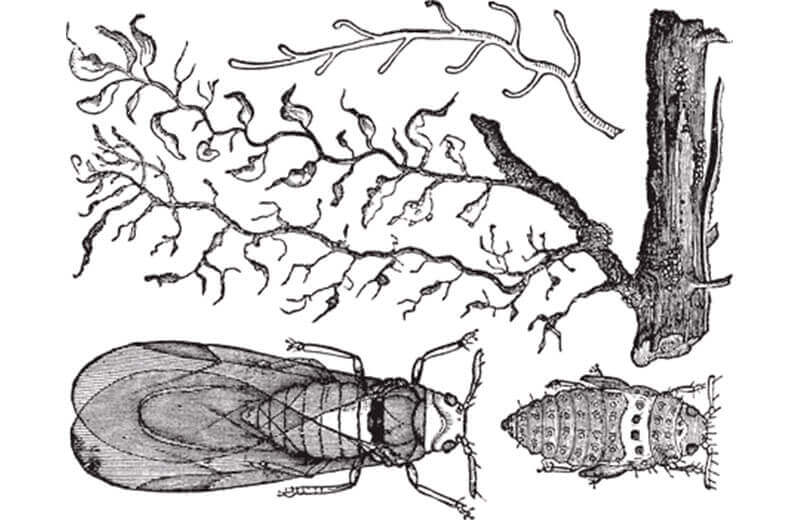

Phylloxera vastatrix - the 'dry leaf devastator'

Death & Destruction

From England to France then to Portugal, the lice marched on, causing severe sickness in the grapevines they infested: leaves yellowed and shrivelled, after which, death was imminent. The mites’ method of attack? Inserting their feeding tubes into the vulnerable root of the European vine and sucking its sap. Eventually, the root would become so deformed that it could no longer draw water or nutrients from the soil and would rot. In effect, the vines starved to death.

In 1868, at around the time the mite arrived in the Port vineyards of the Douro Valley, the French researcher Jules-Émile Planchon gave the pest its name: Phylloxera vastatrix, the ‘dry leaf devastator’. By 1872, Phylloxera had brought many famous Port estates to their knees by decimating their yields. Indeed, that year, the yield of one well-known estate is recorded as having dropped from 70 pipes (barrels) to only one. Today, the memories of this calamitous time linger in the sinister mortórios – the abandoned ruins of ancient terraces never replanted.

Derelict terraces overgrown with vegetation in a mortório

Desperate Times, Desperate Measures

Despite the ruthless might of Phylloxera, there were men willing to stand up to it. One of these was John Alexander Fladgate, who had become a partner at Taylor’s in 1836. Fladgate’s twin passions were viticulture and the beautiful Douro Valley. When Phylloxera started to destroy the two things so dear to him, he was determined they should survive.

By this time, Phylloxera had already destroyed many French vineyards. Desperate times had called for desperate measures. Wooden cranes or giant crowbars were used to uproot diseased vines. The soil was impregnated with various potions including lime or sulphur. Dead toads were buried to draw poison from afflicted plants. However, as time passed, the French growers discovered more effective ways to keep Phylloxera at bay. Realising that they were a step ahead, Fladgate headed to France to learn what methods were being used to control the pest.

Baron Fladgate’s open letter

On his return, Fladgate published his findings and advice in an open letter to the Douro farmers; in recognition of this work, the Portuguese Crown awarded him the title of Baron of Roêda.

Hard Graft

Despite Baron Fladgate’s great efforts, it would be some time before a conclusive solution to the problem was found: the grafting of the European Vitis vinifera onto the resistant roots of native American vines. The huge job of replanting the vineyards of the Douro with grafted stock began in the late 1870s and gathered pace in the 1880s; by the late 1890s, Phylloxera was finally brought to heel.

A grafted vine

Life After Death

Due to the devastation most vineyards had to be completely replanted, but this offered the opportunity to experiment with new grape varieties and techniques. A great example of this rebirth is Quinta de Vargellas. In 1893, when Taylor Fladgate purchased this estate, it was in a state of disrepair and annual production had fallen to no more than 4 pipes. The monumental task of restoring Vargellas to its former glory fell to another Taylor Fladgate partner, Frank ‘Smiler’ Yeatman.

Replanting the vineyard at Quinta de Vargellas

Liquid History

Sadly, we don’t really know whether wines of the pre-Phylloxera era tasted very different from today’s. Wines from that period are extremely rare and those surviving in perfect condition are virtually unheard of. Certainly among the last of these historic Ports is Taylor Fladgate Scion, a cask-aged Port made over 150 years ago.

When it was recently released as a collector’s limited edition, it quickly sold out; when the last drop of it has been drunk, one of the very few remaining voices of the pre-Phylloxera era will be silenced forever.

However, we still have something to look forward to as Taylor Fladgate possesses one of the nest and most extensive reserves of old, cask-aged Ports. This includes some rare wines from the 19th century, concentrated to an almost magical essence by decades of ageing yet still vibrant and full of life. These are the survivors of a bygone age that can never be recreated. So there’s still a chance that, one day, you might be lucky enough to taste an irreplaceable piece of liquid history.